JHI's Associate Director Kimberley Yates travelled recently to South Africa to attend a couple of events hosted by the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape. Since the JHI had partnered with the CHR for a few years, Kim also hoped to explore possibilities for further collaboration. The first event—Puppetry, Pedagogy, Politics and Praxis Workshop—was followed by the Winter School, an annual four-day symposium on critical theory presented by the CHR. This is Kim's blog post about her trip.

Part 1: Why Puppets? Arrival and the Puppetry Workshop

The first thing I noticed was the light. Dazed, after nearly a full day’s flight and a time change of six hours forward, I found my ride and we were hurtling toward Cape Town in a glowing sunset. I couldn’t stop looking at the mountains. They were each a different shade of purple, an Impressionist landscape in three dimensions. The driver shrugged and said there had been a grass fire earlier. He noted, to our left (the passenger side, there) a vast horizon of tiny metal shacks, apparently built from random industrial garbage, and huddled close together. Many had satellite dishes. He called them squatters.

I tried and failed to square the tropical sunlight and palm trees with this display of extreme poverty. As we entered Cape Town, I saw ornate and brightly painted architecture, winding roads and steep climbs and drops, but I noticed also that most properties were surrounded by a high solid wall topped with electric wire, and while there were sidewalks, there were very few pedestrians. We pulled into my hotel, a modest urban 3-star, and I was in a safe oasis. I asked how much for the ride, and he laughed and said he’d been paid already, no charge. I tipped anyhow.

I had come to South Africa to attend a pair of events hosted by the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape. The Jackman Humanities Institute (JHI), had partnered with the CHR for a few years, and I hoped to learn more about how things stood and to think about the possibilities for further collaboration. I spent my first day with Heidi Grunebaum, the Director, and Maurits van Bever Donker, the Associate Director, who drove me out of Cape Town to the site of the UWC and gave me a fast overview of its history: the UWC is South Africa’s national flagship institution in the humanities, founded on the principle of ‘Aesthetic Education’.

I had come to South Africa to attend a pair of events hosted by the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape. The Jackman Humanities Institute (JHI), had partnered with the CHR for a few years, and I hoped to learn more about how things stood and to think about the possibilities for further collaboration. I spent my first day with Heidi Grunebaum, the Director, and Maurits van Bever Donker, the Associate Director, who drove me out of Cape Town to the site of the UWC and gave me a fast overview of its history: the UWC is South Africa’s national flagship institution in the humanities, founded on the principle of ‘Aesthetic Education’.

Located miles outside Cape Town on swamp land, it was a small and unfashionable place, and yet, I thought, perhaps that obscurity provided the privacy that was needed to imagine a post-Apartheid future. It had been designed to reproduce the administration of Apartheid with vocational education for “Coloured” students, but its programming lacked training in the arts, which was reserved for the white universities.

In the 1950s, the rector broke the law and opened registration to all, redefining UWC’s mission with his vision of higher education for freedom. Declaring UWC to be the intellectual home of the democratic left, he inaugurated programming in the arts for its students. It became the intellectual heart of the anti-apartheid resistance, and when Apartheid finally ended, many faculty members exited to participate in the new government.

As we chatted, I gradually perceived the magnitude of the racist violence that Apartheid had imposed: a fully modernized fascist state in which every detail of everyday life was defined and classified in racial terms. The visceral horror of what that experience must have felt like hit me hard. It ended in the early 1990s, during my adult lifetime.

We drove back into Cape Town to see the CHR’s new building, Greatmore. It is a former school that sits on the road that divided “White” and “Coloured” sections of the town. A large and graceful building, it features symmetrical Roman arches and rows of rectangular windows, arranged around an interior courtyard.

We drove back into Cape Town to see the CHR’s new building, Greatmore. It is a former school that sits on the road that divided “White” and “Coloured” sections of the town. A large and graceful building, it features symmetrical Roman arches and rows of rectangular windows, arranged around an interior courtyard.

Originally divided into Boys and Girls halves, the hallways and entrances were arranged so that the genders were separated unless the school’s population was assembled in the central courtyard. It had been abandoned for a few years, and then the government had provided funding for the CHR to renovate it for use as a local arts hub.

The renovation had opened those gendered spaces and disrupted the symmetries a bit, creating shared, sunlit rooms for music, art, puppetry, film, and visiting humanities researchers. It will be a glorious place full of creativity and ideas, designed to invite artists and researchers to cross interdisciplinary boundaries, to be inspired by each other and by the wide blue skies and by the ever-present view of the mountains.

I imagined the room for visiting researchers next year, hardwood floors and high ceilings finished, desks populated with interesting people from around the world who would be alternately working and chatting and learning from the rich mixture of makers, performers, musicians, and other creators around them. Paradise for the imagination! As we left the gated entrance, the question of how to manage security and yet be open to the local public lingered. Reaching the public in Toronto is more a matter of catching their attention than of being prepared for violence. The stakes of public humanities are fresher and more precise in South Africa.

Why Puppets?

The first event was the Puppetry, Pedagogy, Politics and Praxis Workshop. We met in the District Six Homecoming Centre in Cape Town, a pleasant café and converted warehouse that also housed a theatre and museum. (District Six was a part of the city that had been violently cleared and levelled of its Black inhabitants during the 1970s.)

The first event was the Puppetry, Pedagogy, Politics and Praxis Workshop. We met in the District Six Homecoming Centre in Cape Town, a pleasant café and converted warehouse that also housed a theatre and museum. (District Six was a part of the city that had been violently cleared and levelled of its Black inhabitants during the 1970s.)

Around 25 puppeteers from all over the world had come to discuss how and why they did what they did. Adrian Kohler, the co-founder of Handspring Puppet Theatre, hopped up onto the table to demonstrate a series of increasingly large puppets while providing a history of world puppetry from shadow puppets to hand puppets to marionettes to the large-scale mechanics of War Horse and Little Amal.

Premesh Lalu, the inaugural director of the CHR, spoke about the politics of puppetry: the puppet as a mediating object between human and machine that helps us to recuperate human memory, a mechanical object that allows us to rethink the logic of sense and perception and challenges the mechanics of institutionalized racism.

In the afternoon, the Ukwanda Puppet Company, which will be hosted at Greatmore, discussed preparations for a performance for the Barrydale Puppet Parade that will feature Charlotte Maxeke, an extraordinary Black feminist who lived over a hundred years ago. (Her surname is pronounced “Makleke”, with the x pronounced as a Xhosa click). A demonstration of the ”song machine” – a single object that is a multiple-puppet chorus worn as a harness – brought a huge round of applause.

Sculptor Jill Joubert and puppeteer Purav Goswami showed works created for a production of Giraffe Humming, which retold the story of a giraffe sent to India and then on to China as a tribute in the 15th century. The play explores the dissolution of the giraffe’s soul through conversation with its keeper. As the narrative moves from Africa to India to China, the giraffe puppet changes from wooden to fabric to shadows, exploring non-human relations and migration as tragedy, and challenging the boundaries between the mechanical and the artistic.

The next morning, Tito Lorefice discussed his university-level training program for puppeteers in Buenos Aires, Argentina. To demonstrate some basic pedagogical techniques, he gave each of us a 12” dowel and then paired us as puppet and puppeteer. Here’s what I wrote in my notebook afterward:

The next morning, Tito Lorefice discussed his university-level training program for puppeteers in Buenos Aires, Argentina. To demonstrate some basic pedagogical techniques, he gave each of us a 12” dowel and then paired us as puppet and puppeteer. Here’s what I wrote in my notebook afterward:

I am stiff, confused. We take a moment to be in contact with those two sticks again. Long smooth dowels. I concentrate on sticks. I am sticks. I rise, stretch tall, embrace myself, take tiny baby steps in the darkness. I turn and turn again, a full twirl. We are paired with another puppet and puppeteer. My hand rises, touches, is touched. My face is stroked. Hands touch hands, rise and fall. We are dancing, moving together in time. Slowly, slowly, we separate. I am myself again.

Now I am controlling. My puppet is beautiful. He smells like lemons. So many mechanics. I can’t quite see both his hands at once. I move him forward and we turn to avoid a collision, but now he is off balance and corrects on his own. I lift his arms, drop him down into a bend. We pair again. I touch another puppet’s hair, face, neck, using his hand. We bring both sets of hands into contact, but they keep falling apart. Dancing is impossible. We part. I cross his arms over his chest, and slowly, slowly, we separate and meet in time and space as individuals again.

This was an utterly magical experience! It was a basic trust exercise, but it taught me how much of the puppeteer’s job is to move their consciousness into the puppet, to relate as though with another living being. Tito said that puppets aid in communication, when putting things into words is difficult. They are prominent in human rights protests, helping to express things about the trauma of dictatorship.

The puppeteer is a good mirror for society: we train them to look inside, beyond manipulation to interpretation. Puppets are poetry – knowing grammar is helpful, but it won’t get you all the way. There is a vocabulary of movement, like playing a musical instrument. We don’t just manipulate a guitar, we train the body and mind and soul of the puppeteer like a dancer to hear what the material says, to make it real.

The rest of the workshop passed in a blur because I was processing this intense experience. We heard from NGOs who use puppets to convey basic skills of community mobilization, medical response, and negotiation. The University of Toronto’s Larry Switzky discussed Mark Fisher’s distinction of the weird and the eerie as a way to approach the uncanny valley of puppetry, noting the resonance with Indigenous ways of seeing that approach all physical objects as inherently alive.

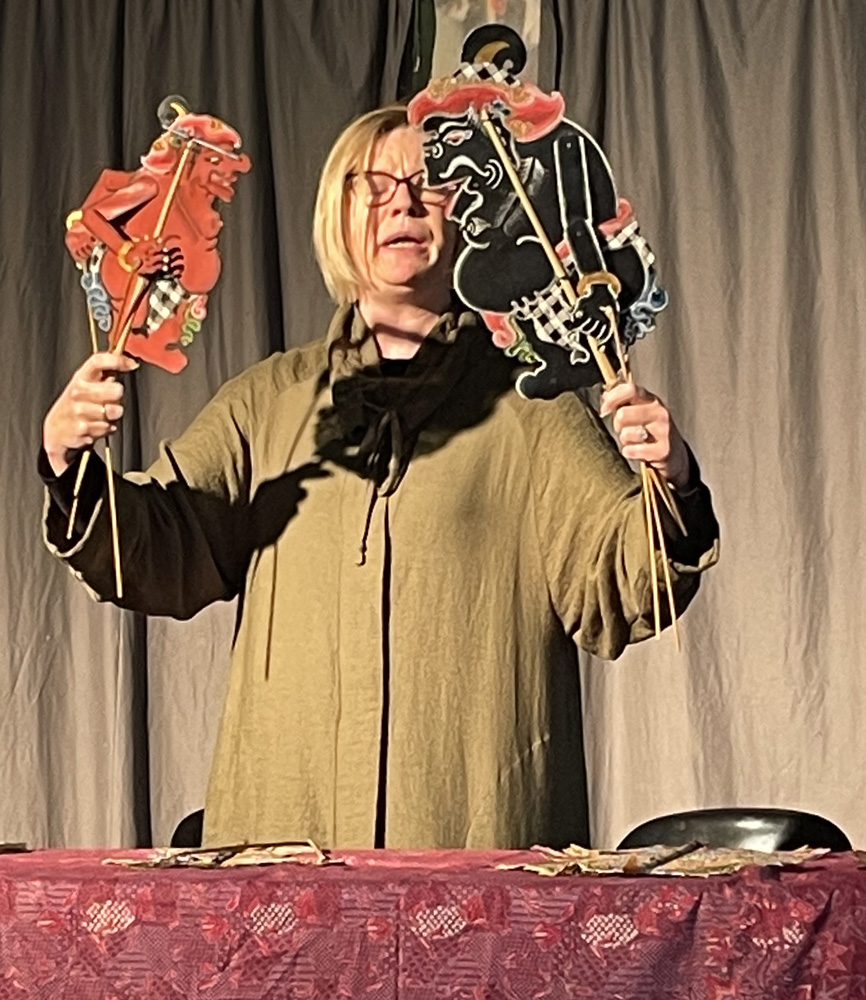

On the last day, Jennifer Goodlanderdiscussed East Asian puppets, ending with a demonstration that told traditional Balinese stories of the god Arjuna. Her training as a dayang (puppeteer) included a ritual marriage to her puppets; when she lifted the leaf and invoked the world into existence, her voice was huge and powerful. She performed a brief clown episode and then discussed improvisation and the constant negotiation between contemporary and traditional that her practice requires, noting that outside funding tends to freeze traditions, which paradoxically is a modern phenomenon.

On the last day, Jennifer Goodlanderdiscussed East Asian puppets, ending with a demonstration that told traditional Balinese stories of the god Arjuna. Her training as a dayang (puppeteer) included a ritual marriage to her puppets; when she lifted the leaf and invoked the world into existence, her voice was huge and powerful. She performed a brief clown episode and then discussed improvisation and the constant negotiation between contemporary and traditional that her practice requires, noting that outside funding tends to freeze traditions, which paradoxically is a modern phenomenon.

In the final presentation, puppeteers from Net Vir Pret demonstrated Duke the zebra and Olosongulolo the caterpillar, who had performed in the most recent Barrydale parade. The lines between companies seemed blurred, but it was clear that Handspring was the first, and Net Vir Pret was its lineal descendant, and Ukwanda were the current student puppeteers to be hosted at Greatmore.

Why puppets? They defy categorization and definition, and if they have one consistent property, it is their playful tendency to figure out how to bend the rules. Somehow, their nonhuman nature brings out the best in human nature: honesty, courage, joy, laughter. Puppeteers are lovely folks. I was completely welcomed even though I was the only one in the room with no experience of puppetry. Skin colour was irrelevant: what brought us together was curiosity and creativity and the thrill of performance. Canadians might imagine children’s entertainment like Mr. Dressup or the Muppets, but puppetry is ancient and powerful and inherently subversive, and there is a short and direct line from puppeteering to AI animation. This generous and intensely intellectual experience will stay with me for a long time.

Part 2: Global Encounters at The Winter School

I spent the second part of my visit in the Winter School, which is an annual four-day symposium on critical theory presented by the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape. The Winter School is normally presented in the July or August, which is winter for the southern hemisphere, but this year, given that it had been disrupted by pandemic measures for two years, the desire to hold it sooner and in person pushed the dates into October, which is springtime.

I saw a lot of flowers in gardens and hedges that are florist-shop exotics in Toronto and the weather was warm and sunny, a pleasant hiatus from my own winter’s approach. The Winter School is a theory-infused examination of the humanities and arts that is planned on a specific theme each year: this year’s theme was The Minor, a response to a galvanizing lecture presented at last year’s event by Ajay Skaria, “The Subaltern and the Minor; for Qadri Ismail”.

The CHR is a vigorous creator of online content, and each session of both the puppetry workshop and the Winter School was professionally video recorded. This commitment to creating a record of their activity impressed me because I know how much these recordings cost and how long it takes to edit and post them. My thoughts here are impressions rather than an attempt to capture every moment because those recordings will appear eventually on the CHR website.

Heidi Grunebaum introduced the Winter School with an invitation to “think more deeply, listen more closely, and engage more powerfully… with what freedom means post-Apartheid. What arts and intellectual engagements grew up in the places of Apartheid’s regime?” The sessions were organized as examinations of the concept of the Minor in relation to each of the arts in turn – film, reading, analysis, puppetry, literature, art – and it became clear that the critical apparatus of Freud, Deleuze, Guattari, Lacan, and Fanon provided the threads that illuminated our look into the edgy shadows of creation and interpretation.

Heidi Grunebaum introduced the Winter School with an invitation to “think more deeply, listen more closely, and engage more powerfully… with what freedom means post-Apartheid. What arts and intellectual engagements grew up in the places of Apartheid’s regime?” The sessions were organized as examinations of the concept of the Minor in relation to each of the arts in turn – film, reading, analysis, puppetry, literature, art – and it became clear that the critical apparatus of Freud, Deleuze, Guattari, Lacan, and Fanon provided the threads that illuminated our look into the edgy shadows of creation and interpretation.

Ross Truscott took us from Freud to his disciple, LaPlanche, to Fanon to consider Apartheid as an obsessive compulsion to divide that masks a desire for the Other rooted in the memory of Black nannies who raised white children. Premesh Lalu offered a terminology from 1840s evolutionary science, “the consilience of induction” to describe the moment of surprise when information jumps from one field to another, the serendipitous interdisciplinary encounter that the humanities seek when they challenge disciplinary categorizations and boundaries. Musician Reza Khota described composition as a manipulation that subverts the visual by pushing the listener’s imagination out of the visual and the critical and into aporia, a space at sea that recomposes into art.

Siba Grovogui’s keynote lecture tackled the old trope that “Emotion is reason, just as Reason is Hellenic” by examining the concept of sympathy. Intellectual processes begin in emotion; while the Golden Rule (do unto others) supposes that you know what is good, sympathy is relational and often political. Rather than a Western canonical understanding that dissembles, forecloses outcomes, and leaves out half of human history, he repeated Gandhi’s call to “Be the change you want to see” and asked exactly what self-identified whites were willing to forswear? Beyond the fear of a new order, how do we respond? Sympathy is granted to the former oppressor as an act of radical equality.

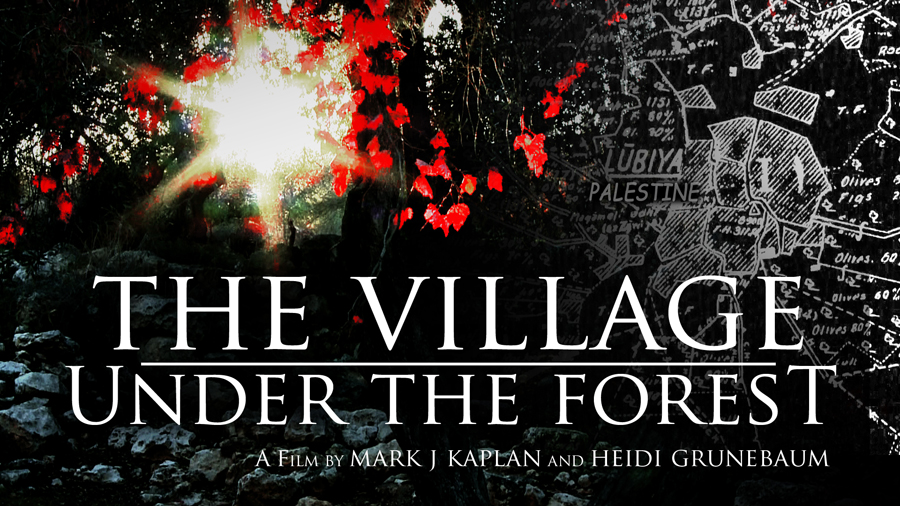

On the second morning, a pair of short documentary films (A Ship from Guantanamo by Dara Kell and Veena Rao and The Village Under the Forest by Heidi Gruenebaum and Mark Caplan) were shown. The second of these hit me hard with a personal revelation. It examines a site in Israel called the South Africa Forest, a publicly accessible parkland that grows over the ruins of a Palestinian village. Each year on 15 May, Nakba Day, the former villagers visit to remember this place. Their story of loss is told as a microhistory of the Palestinian occupation, and within a dawning recognition by the Jewish narrator of the violence of settler occupation, which has deep parallels with Apartheid South Africa.

I thought about the land acknowledgement that I hear before each JHI event, and the pain of loss contained in this short paragraph washed over me. As a white settler in what is now called Canada, despite many seminars on cultural competency, and the opportunity to work with Indigenous fellows every year, I had never viscerally comprehended this pain of loss, of erasure, of state violence in the name of safety and environmentalism. I felt shame and a powerful desire to forswear.

The discussion that followed examined documentary filmmaking as a negotiation of the paradoxical tension between documenting reality and artistic voice, as a process more important that the product (which is never ‘final’ because the story always goes on, and the filmmaker becomes a part of the community they record.) Documentary relies on the Minor as subject and may commodify the Minor by turning it into image, so the filmmaker has an ethical responsibility to their subjects and should ask ‘what would you like to see? What would you like not to see? Who is this story for? How would you like to distribute it?’ Minor cinema can fulfil this responsibility by forcing the audience to recognize traces of the production process, by including signs of its own construction.

The highlight of Day Three was Eve Patten’s public lecture, “Ireland, England, and the paradox of ‘minor literature’” . She began with Dipesh Chakrabarty’s claim that “majority and minority are not natural entities: they are constructions and status changes in time.” She discussed Zoë Wicomb’s recent novel Still Life, which is a playful contesting of English colonial literary history. Minority and majority change positions in relation to each other; in the 1900-1950 period, as the Empire shrank, English literature aspired to minority status, self-minoritizing into folklore, peasant-pastoral, and medievalism.

This form of self-decolonization was magical thinking produced by the weariness of imperial collapse, an ersatz minority discourse that borrowed the imagery of a ‘small island’ from Ireland by separating England (the here) from the British Empire (there), often characterizing itself as a child. The medieval was weaponized as Irish feudal structures got used to describe African colonies in the 1920s. Sinister applications of this imagery appeared in the recent Brexit campaign, in the desire for a safe space in time.

Patten’s elegant lecture moved through major and minor writers in England and Ireland to conclude that “there is an enlargement of literary space that accompanies liberation” – Irish writing rises above national consciousness and ethnic essentialism, ceases to be minor, becoming transnational and nomadic. I was inspired to find a copy of Still Life, which I have been savouring. There was so much to think about in this talk that I have been pondering ever since: my own doctoral work was largely about English medievalists, and the shadow of a fading empire impacts my impressions in significant ways.

The challenge of an intellectual revelation is that it disrupts one’s capacity to absorb more stimulation. In the whirl of talks, panels, and conversations that followed, my mental fatigue grew into a blur of coffee and incoherent notes. John Mowitt’s meditation on the minor as a musical definition, and Lebogang Mokwena’s discussion of the transition of Ubuhle beadwork from craft to narrative fine art in the post-Apartheid context were outstanding. We ended with a dinner for all participants at an Ethiopian restaurant, a happy roar of post-presentation joy and delicious finger foods along with an abundance of excellent South African wine.

Part 3: Johannesburg, Haunted Africa, and the Hunt for the Real

I was on a plane from Cape Town to Johannesburg the next morning. The original plan had been to stay with the family of a friend, but circumstances made this infeasible, so she booked me into a B&B in the nice part of town. It was an enormous Gilded Age mansion called The Great Gatsby with outbuildings, servant stairs, and Jacaranda trees in bloom. I arrived before my room was ready, so the hostess lodged me in an isolated suite at the top of a long flight of outdoor stone stairs. As I reached the last step, I tripped and fell flat on my face. My phone shattered, and my camera and glasses were damaged. A bruise slowly bloomed on my nose where my glasses sat.

I was on a plane from Cape Town to Johannesburg the next morning. The original plan had been to stay with the family of a friend, but circumstances made this infeasible, so she booked me into a B&B in the nice part of town. It was an enormous Gilded Age mansion called The Great Gatsby with outbuildings, servant stairs, and Jacaranda trees in bloom. I arrived before my room was ready, so the hostess lodged me in an isolated suite at the top of a long flight of outdoor stone stairs. As I reached the last step, I tripped and fell flat on my face. My phone shattered, and my camera and glasses were damaged. A bruise slowly bloomed on my nose where my glasses sat.

In fatigue and some pain, I spent the next couple of days sleeping, and instead of exploring South Africa’s capital city, I explored this strange old mansion, imagining it full of whispering servants and a screaming mistress, glittering with secrets and pain. The past seemed to peer out at me from every mirror. One night I locked myself out of my room; the next, I got locked into it. (Skeleton keys were not my friends.)

The food was excellent, and as I recovered I made friends with the other lodgers around the table: an Afrikaaner businessman who was involved in water filtration and hunted big game, a gay Austrian physicist who studied sunspots, and an elderly English-descended woman who was in the city to deal with her mother’s oncologist. The locals forswore Apartheid, of course. But there were sideways hints of yearning for the childhood life that was gone, for the things that no longer tilted to their advantage. When a new (Black) lodger arrived, the hostess mentioned him as “an African gentleman” to our group. The others turned away while I engaged him in conversation. I thought how fragile liberation is, when nice people can go on longing for the return of the regime thirty years later, quietly re-enacting its categories.

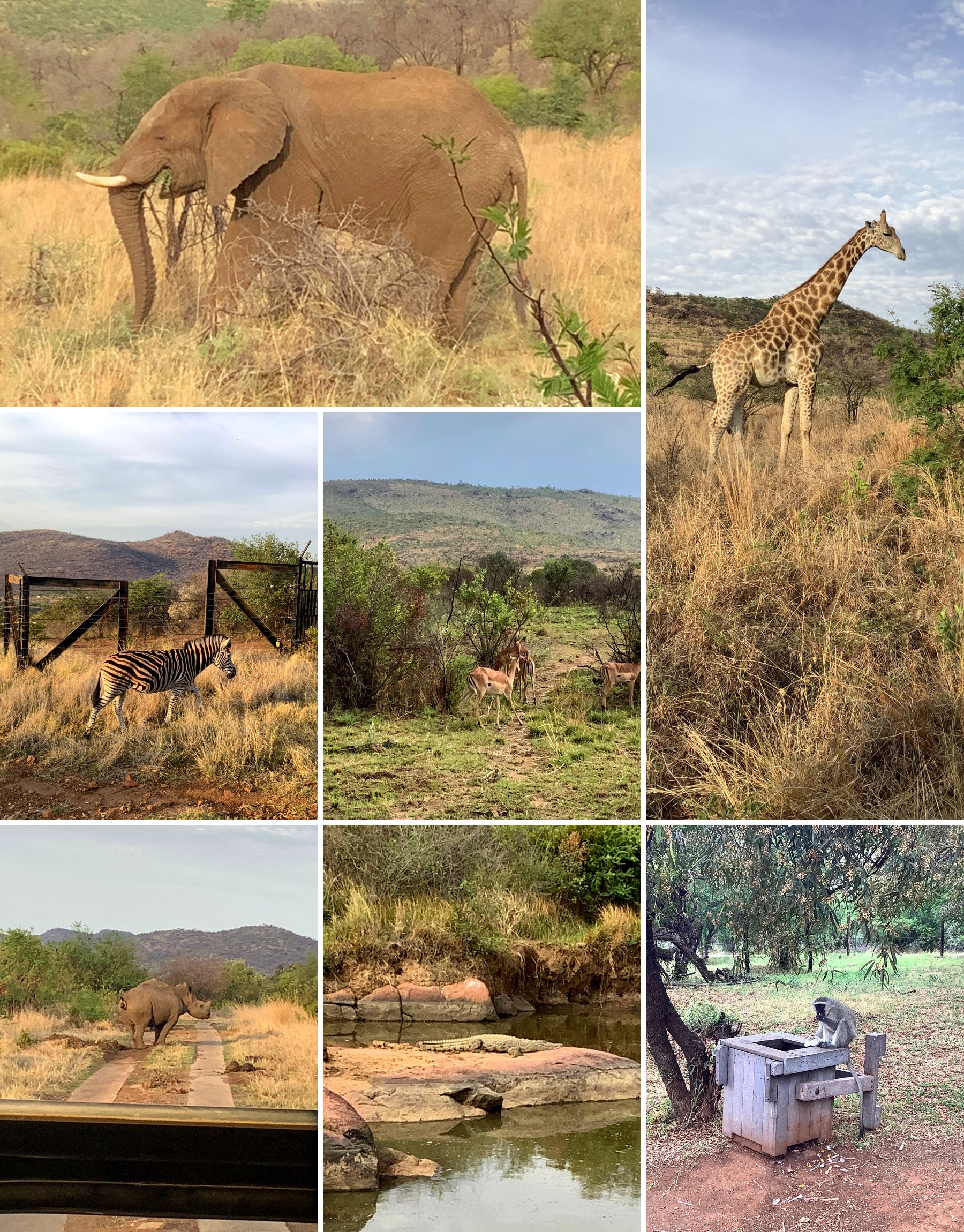

When my head was clear, my friend turned up with a car and another friend, and we drove for a few hours to a game reserve in the North West province. We checked into a hotel-like lodge and booked a pair of safari drives, one at sunset, and the next at sunrise the next morning. For three hours each time, we bumped and bounced over rough paths and we saw elephants , zebras, white rhinoceros, giraffes, a crocodile, a monkey, a herd of springboks and, although they were impossible to photograph, a pride of female lions in the dark, and a faraway cheetah. Was this the ‘Real Africa’? It was thrilling, and our guides were both knowledgeable and candid about the realities of wildlife management. On the way to our room in the evening, a small brown snake on the walkway sidled toward us, lifting its head. We skipped around it, leaving it to its own devices. The next morning, our guide said that it was a baby cobra, and it was lucky that none of us had been bitten because it would have been fatal. On the way back, we drove past Sun City, the gambling resort made famous by Steve Van Zandt in 1985. It’s still there. It’s expensive.

On the last day, my friend showed me Constitution Hill, where the post-Apartheid constitution was written in Johannesburg. A new country was born on the site where dissidents had been incarcerated for a hundred years. The Constitutional Court is a beautiful mid-century modern building that was designed in every detail to resonate with the struggle for freedom. A series of exhibition pieces elevated the memory of that struggle into art. We peered into the courtroom itself, where lawmakers were at work in COVID-safe glass cubicles arranged in a sweeping semi-circle. Outside, a group of Black women protesters were camped. They sang and beat pop bottles to raise awareness for their request for land reparations. South Africa is complicated and creative and contradictory, saddled with historical weight and extremes of wealth and poverty, full of darkness and light, and surging with creativity and imagination. I’ve never encountered a place like it, and I hope I’ll have another chance to visit.