On February 14 and 16, 2024 the JHI's Program for the Arts is pleased to co-sponsor Embroidering Absence: War Memories of Salvadoran Women Refugees—a talk and public exhibition exploring how Salvadoran women, forced into exile during the civil war (1980-1992), harnessed the power of embroidery to confront and heal from absence. In this interview, María Méndez—co-curator and Assistant Professor, Political Science—provides insight into the significance of using embroidery as a means of conveying complex narratives, the therapeutic aspects of the medium in confronting trauma, and the global impact of disseminating these artworks.

JHI: Can you provide some background on how the idea for Embroidering Absence came about?

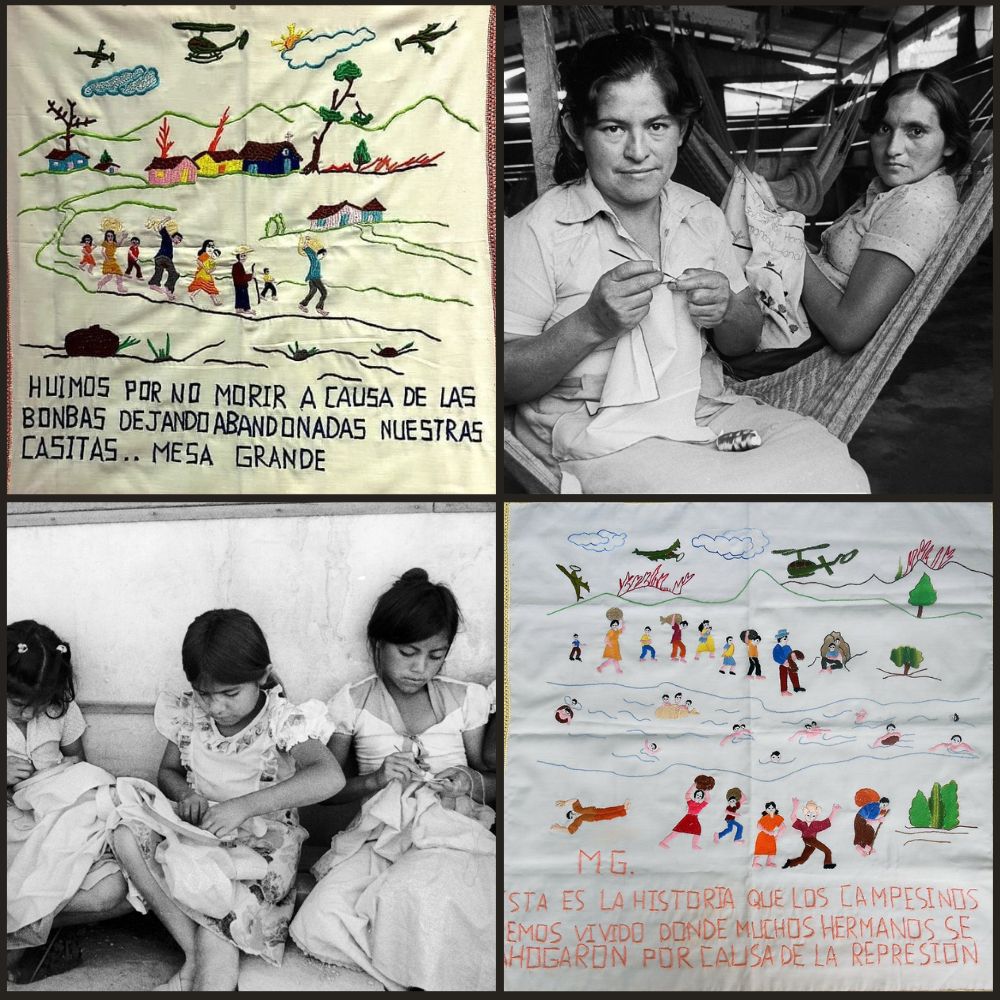

MM: The concept for Embroidering Absence emerged during a visit to El Salvador, where I encountered embroidered pieces by Salvadoran women refugees at the Museum of Word and Image (MUPI). These pieces told powerful stories about the lived experiences of the civil war, and I thought it would be meaningful to bring these artworks to Toronto, particularly considering the sizable Salvadoran diaspora in the city. Moreover, given the political climate in El Salvador, where memories of the civil war are being silenced, I also saw the exhibition as a good way to counteract that historical amnesia.

JHI: How do the embroidered pieces convey complex narratives that may not be easily expressed through other mediums?

MM: In El Salvador, embroidery has deep roots in peasant culture, providing women, particularly those without literacy, a means to communicate their experiences through art. It also serves as a unique form of expression, especially for those who find it challenging to articulate their feelings verbally. For example, a Salvadoran woman shared her difficulty in discussing the loss of her children during the war, but through embroidery, she could convey her emotions without using words.

JHI: Can you elaborate on using embroidery as a medium for confronting and healing from the experiences of exile and conflict?

MM: Embroidery is a vital process for confronting and healing from the traumas of exile and conflict. The tactile nature of handling fabric and thread, the rhythmic motion of the needle, and the focused attention required for stitching offer a therapeutic outlet for many who have endured trauma. Weaving allowed individuals to temporarily escape their worries and express painful memories that were hard to put into words. Moreover, the act of creating art amidst destruction provided a sense of empowerment to those who felt powerless in the face of cruelty. This empowerment fostered a sense of community, as people came together to embroider and share their experiences. Collaborative embroidery sessions during and after the civil war offered a supportive environment where individuals could connect, learn from each other, and find relief in collective expression.

JHI: The exhibition aims to foster international solidarity. How has the global dissemination of these embroidered pieces contributed to raising awareness and fostering connections among diverse audiences worldwide?

MM: These embroidered pieces, like the arpilleras from Chile in the 1970s, were used to expose the brutality of the Salvadoran army, heavily supported by the US government. In the 1980s, when information about El Salvador was heavily censored, these embroideries served as silent witnesses of the situation in the country, smuggled out in the clothes of humanitarian workers. They reached countries like Mexico, Spain, Italy, Germany, and the US, where they became crucial in raising awareness. One such embroidery even played a pivotal role as evidence in a political asylum hearing in the US, challenging the denialism of the government and becoming a poignant testament to the realities of the war.

JHI: What do you hope your visitors/participants will take away from Embroidering Absence?

MM: I hope visitors and participants will gain an understanding of the vital role of women's memory work in reclaiming the past, healing wounds, and shaping the future. I also hope they will gain a new perspective on war from women's experiences. These embroideries not only depict the hardships of conflict but also tell a broader and deeper story. They invite us to explore a rich emotional landscape, filled with moments of hope, joy, compassion, friendship, and generosity that shine through despite the shadows of war. These narratives transcend the pain and suffering, reminding us that war does not define all aspects of human experience.

JHI: How did you hear about the JHI's Program for the Arts and what made you apply?

MM: I discovered the JHI's Program for the Arts through their newsletter and was eager to apply for initial funding to bring Embroidering Absence to Toronto.

JHI: Can you say a few words about your experience with the Program for the Arts so far for others thinking of applying?

MM: My experience with the Program for the Arts has been fantastic. The team, including talented publicists like Sonja, provided invaluable support, with promotion and outreach for my events. If you have a budding idea, like the one I had, I highly encourage you to apply. It's a wonderful opportunity to bring your vision to life with their assistance.

Embroidering Absence: War Memories of Salvadoran Women Refugees is comprised of a talk on February 14 and an exhibition on February 16. The events are open to all, but we request that you register ahead of time. Supported by the JHI’s Program for the Arts, CDRS, Department of Political Science, Latin American Studies program, Western University, The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Surviving Memory in Postwar El Salvador project, and MUPI, the exhibition aims to foster a deeper appreciation of women’s memory work.